Dehumanization, Death, & Design

Rehabilitation Through Architecture

By Katya Huzau

Mass Incarceration

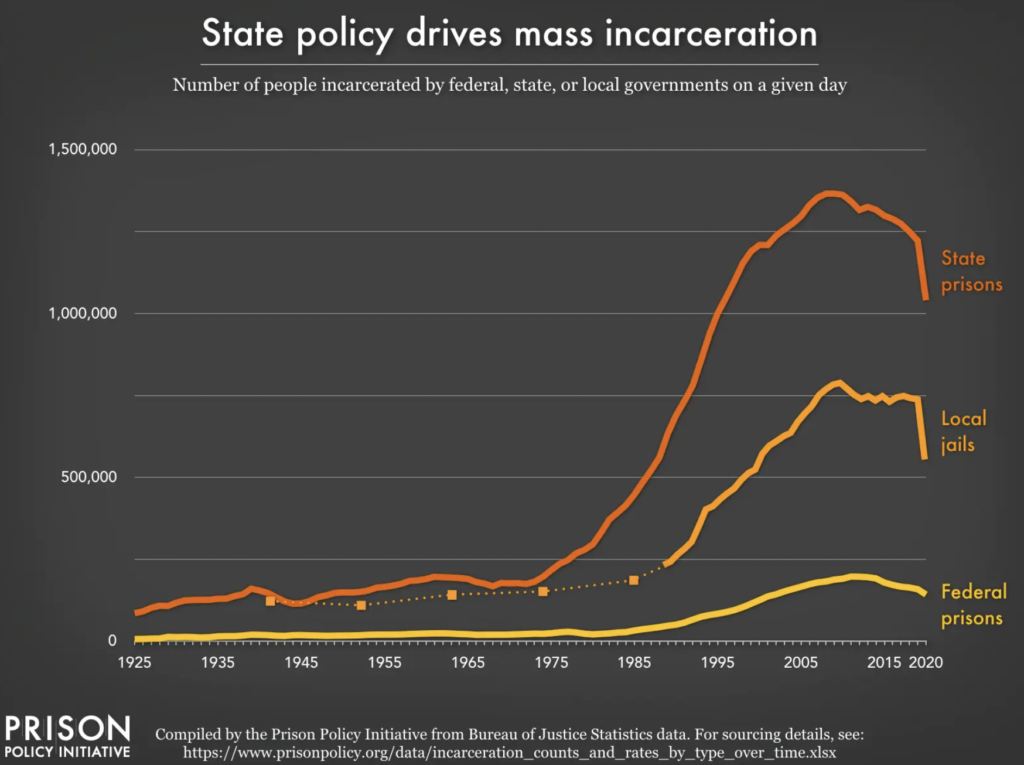

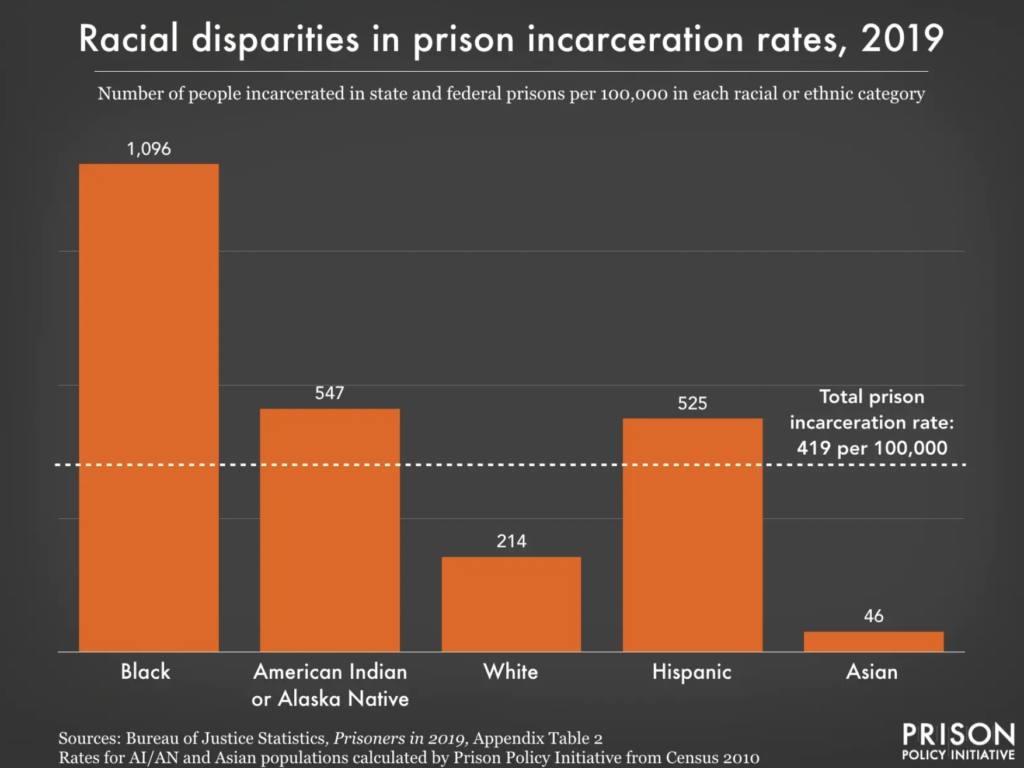

There is a mass incarceration problem in the United States. Currently, almost 2 million people are imprisoned—that’s more than any other country in the world. But how exactly did we get here? It all began in the 1970s, when Richard Nixon was in office. President Nixon first introduced the law-and-order, tough-on-crime, and war-on-drugs policies that inspired his two successors—Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton—to sign into law two bills that would see the total population of prisons and jails rise exponentially and further exacerbated the severe racial discrimination and disparity we see within our justice system, of which punishment is an integral component.

Prison Design

In 1816, a new penal system would emerge out of New York that would influence the design and philosophy of the modern prison system of today—that for punishment to be just, it needs to contain an element of suffering. Taking inspiration for solitary confinement from Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary, the Auburn System, named after Auburn Prison, was designed to punish the incarcerated through imprisonment itself. Its goal was to humiliate, terrorize, and control prisoners by keeping them under constant surveillance, stripping them of their identity, threatening, and forcing them to spend their days silently working and their nights confined to their cells, which were small and opened out toward central spaces or hallways where guards could constantly keep watch of them.

Still, not much has changed regarding the architecture of San Quentin’s cell blocks, the last of which was built in 1934. Like most prisons in America, they are designed like fortresses made of concrete and steel, lit by fluorescent light, surrounded by high walls and barbed wire fences, and painted in sterile, cold whites and grays—all of which are clearly represented in Bitner’s photograph. Prison architecture is meant to isolate and dehumanize inmates, and restrict any fostering of community and societal norms, yet we expect them to join society rehabilitated—this is just not possible.

An average cell within San Quentin’s Adjustment Center, which houses death row inmates deemed too dangerous to be in East Block

Take a virtual tour of San Quentin’s cell blocks

The yard at San Quentin where inmates housed in general population are able go

Prison is a second-by-second assault on the soul, a day-to-day degradation of the self, an oppressive steel and brick umbrella that transforms seconds into hours and hours into days.

Mumia Abu-Jamal, currently serving a life sentence in Philadelphia

Time for Change

If the U.S. intends to encourage reform within its prisons, it needs to incorporate architecture that promotes one’s health, safety, and humanity. As encouraged by the ADPSR, no longer should architects design such spaces that “violate human life and dignity.” Instead, inspiration should be taken from Scandinavian countries, which operate prisons based on the philosophy that community, safety, education, and compassion is needed to create change; and furthermore, are proven to successfully rehabilitate inmates at much higher rates than the U.S.

Already, a handful of prisons throughout the U.S. have begun, or plan to, implement design that rejects the “cruel, inhuman [and] degrading” practices of the past, like San Quentin. At Pennsylvania’s SCI Chester, incorporating Scandinavia’s approach to corrections has enabled inmates to “work through trauma [they’ve] experienced with support from other inmates and the officers,” for there’s “more sense of community” that allows “the guys…to look out for each other more, help each other more,” making it clear that rehabilitation stems from humanity.

Sources

ADPSR. “Prison Architecture.” ADPSR. Accessed November 2023. https://www.adpsr.org/prisonarchitecture.

Benko, Jessica. “The Radical Humaneness of Norway’s Halden Prison.” The New York Times, March 26, 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/29/magazine/the-radical-humaneness-of-norways-halden-prison.html.

Bitner, Rona. Folsom Prison Represa. August 25, 2015. Rhona Bitner. https://rhonabitner.com/listengallery/m0kcoylm7ssi2xrdfkwg1khab9r5e2.

Delaney, Ruth. “Reimagining Prison – Vera Institute of Justice.” Vera Institute of Justice, 2018. https://www.vera.org/downloads/Reimagining-Prison_FINAL2_digital.pdf.

Engstrom, Kelsey V, and Esther F. J. C. van Ginneken. “Ethical Prison Architecture: A Systematic Literature Review of Prison Design Features Related to Wellbeing.” Sage, Space and Culture, 25, no. 3 (June 22, 2022).

Fowler, Megan. “The Human Factor in Prison Design: Contrasting Prison Architecture in the United States and Scandinavia.” Essay. In The Expanding Periphery and the Migrating Center, 373–80. Associate of Collegiate Schools of Architecture, 2015.

How Norway designed a more humane prison. YouTube. Vox, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5v13wrVEQ2M&ab_channel=Vox.

James, Kayla, and Elena Vanko. “The Impacts of Solitary Confinement.” Vera Institute of Justice, April 2021. https://www.vera.org/publications/the-impacts-of-solitary-confinement.

Jeremy Bentham’s ‘perfect’ prison | The Panopticon. YouTube. Aeon Video, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uO4hJVYEJ6I&ab_channel=AeonVideo.

Lindh, Tomas, and John Stark. Prison Project: Little Scandinavia. YouTube. Swedish Television SVT, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gTC1KI0STIY&ab_channel=JohnStark.

Mullane, Nancy. “The Adjustment Center: Where No One Wants to Go.” KALW, October 22, 2012. https://www.kalw.org/show/crosscurrents/2012-10-22/the-adjustment-center-where-no-one-wants-to-go.

Mullane, Nancy. “Walking Death Row at San Quentin State Prison.” KALW, April 29, 2013. https://www.kalw.org/show/crosscurrents/2013-04-29/walking-death-row-at-san-quentin-state-prison.

Shafer, Scott. “Can Newsom Really Transform San Quentin into the ‘Nation’s Most Innovative Rehabilitation Facility’?” KQED, July 28, 1970. https://www.kqed.org/news/11956776/can-newsom-transform-san-quentin-prison-into-the-nations-most-innovative-rehabilitation-facility.

Stryker, Alyssa. “In California Death Row’s ‘Adjustment Center,’ Condemned Men Wait in Solitary Confinement.” Solitary Watch, April 13, 2016. https://solitarywatch.org/2016/04/13/in-californias-death-rows-adjustment-center-condemned-men-wait-in-solitary-confinement/.

Virtual Tour Inside San Quentin’s Death Row. YouTube. Los Angeles Times, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UA6YaAOTQHY&ab_channel=LosAngelesTimes.

Wessler, Mike. “Updated Charts Provide Insights on Racial Disparities, Correctional Control, Jail Suicides, and More.” Prison Policy Initiative, May 19, 2022. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2022/05/19/updated_charts/.