Only A Facade:

Great Housing Mission Venezuela

Evaluating the Housing Mission’s Impact on the Venezuelan Capital

By Sofia Isabel & Drew Niewinski

The Great Housing Mission Venezuela is a government project publicly announced to foster social inclusion and eradicate the strong classist divides in the city of Caracas and the country. However, the Chavista regime used it as a mask to pocket funding money while deceiving the public with large and impressive building facades and suspiciously high numbers of houses delivered that had no backing other than “the president assures it”.

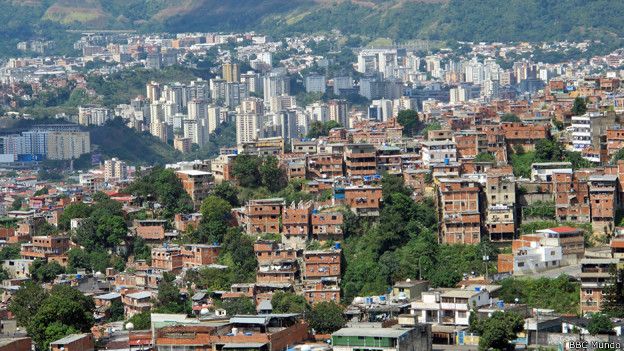

Launched in 2011, the Great Housing Mission Venezuela, known by its acronym in Spanish, GMVV, began quick construction starting in the capital (Caracas) and eventually spreading to other states. The plan claimed to be straightforward: the government would construct buildings and neighborhoods in empty, unused land (public or private) which would provide formal and adequate housing for citizens and their families living in the city’s informal settlements. Once these were built, those living in marginalized communities would be relocated at no cost to their new apartments in the city, improving their lives by placing them closer to work opportunities, schools, and public transportation. This would insert them back into society and erase the present socioeconomic divide.

2020 in Caracas, Venezuela. (Photo by Carlos Becerra/Getty Images)

In reality, many relocated residents took advantage of this new opportunity. They used it as a way to truly better their lives as Mr. Alvarado points out in the audio above. As the GMVV continued construction and began to move in the new residents, the surroundings of the mission’s buildings began to be affected by the negatives, which resulted in the opposite of what the regime once advertised.

Original residents of the city began to avoid the mission’s neighborhoods and its inhabitants, and eventually, both groups would be as socially separate from each other as possible. The increasing crime and lack of regulations in the mission’s neighborhoods made Caracas’ residents reject its inhabitants while seeing them guilty of bringing more chaos to the city. This did not sit well with the mission’s inhabitants, and feeling rejected only led them to accept the label given to them and continue displaying the same behavior they had in their previous settlements.

However, according to current residents of Caracas, the GMVV did not successfully achieve its goal of social integration, at least not as widely as it intended.

Apart from the inadequacies of the housing units delivered, it seems the residents were also not given any set of rules or regulations regarding the use of these buildings.

The informal housing that these marginalized communities had previously lived in was often nuclei for crime, prostitution, and additional informal businesses. (“10 Facts about Slums in Venezuela“) The units in these communities were also erected completely or partly by their residents, which resulted in a system of independence where no one questioned each other’s activities inside their units. Many of those who were relocated brought this same lifestyle into their new homes and neighborhoods and, therefore, into the city. Crime rose in the areas surrounding these buildings and in the city itself, where robbery, drug dealing, and shootings became more common. More on the safety conditions of the neighborhoods here.

Mrs. Requena, who also provided testimony for the podcast above, refers to this phenomenon as “bringing the barrio down to the city”.

The GMVV ultimately served to create isolated and socially segregated neighborhoods that stick out like a sore thumb in the city, both because of the buildings’ looks (as explained in the podcast above) and because of the population’s lifestyle. The new inhabitants did not assimilate into the habits of the city, which does not come as a surprise given that their new residences were given out for free, without rules or conditions, so people did not have any incentives and therefore motivation to assimilate the city’s way of life.

Bibliography

• BBC News Mundo. (2015, April 16). Cómo se vive en las “casas de Chávez.” BBC News Mundo. https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias/2015/04/150310_venezuela_mision_vivienda_chavez_dp

“Buildings of the Housing Mission Crumble Just like the ‘Revolution.’”

• La Patilla, September 7, 2017. https://www.lapatilla.com/2017/09/07/edificios-de-la-mision-vivienda-se-desmoronan-al-igual-que-la-revolucion-impactantes-imagenes/.

• Cariola, Cecilia, Beatriz Fernandez, Beate Jungemann, Rosaura Sierra, and George Azariah-Moreno. “New Processes of Territorial Integration Partner: Impacts of the Great Mission Housing Venezuela in the Urban Segregation of the Metropolitan Caracas.” Cuadernos Del Cendes 31, no. 86 (08, 2014). https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/new-processes-territorial-integration-partner/docview/1761678774/se-2.

• Con la entrega de 20 viviendas multifamiliares GMVV reivindicó a familias tachirenses – Ministerio del Poder Popular para el Hábitat y Vivienda. (n.d.). https://www.minhvi.gob.ve/?p=3170

• Crónica Uno. (2015, August 6). A la Misión Vivienda de La Paz no le dicen “Rodeo I” de gratis. Crónica Uno. https://cronica.uno/a-la-mision-vivienda-de-la-paz-no-le-dicen-rodeo-i-de-gratis-2/

• Crónica Uno. (2022, November 22). 32 familias en riesgo por filtraciones y deslizamientos en urbanismo “Hugo Chávez” de Playa Grande. Crónica Uno. https://cronica.uno/32-familias-en-riesgo-por-filtraciones-y-deslizamientos-en-urbanismo-hugo-chavez-de-playa-grande/

• Gibbs, Stephen. “In Venezuela’s Housing Projects, Even Loyalists Have Had Enough.” Venezuela | The Guardian, February 3, 2020.https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/may/21/venezuela-unrest-chavistas-maduro-protests-shortages

Gobierno de Calle en marcha. (2016, June 13). Chávez siempre Chávez. Lanzamiento de la Gran Misión Vivienda Venezuela GMVV. 30 de abril 2011 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b7t1-RGQtNc

• International Crisis Group. “Venezuela: Tipping Point.” International Crisis Group, 2014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep32120.

Mallett, Ryan. “Housing in Venezuela Could Be About to Get Bad, Really Bad.” teleSUR English, January 15, 2016. https://www.telesurenglish.net/analysis/Housing-in-Venezuela-Could-Be-About-to-Get-Bad-Really-Bad-20160115-0024.html.

• Marx, Benjamin, Thomas Stoker, and Tavneet Suri. “The Economics of Slums in the Developing World.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 27, no. 4 (2013): 187–210. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23560028.

• “El Universal: Obreros de La Misión Vivienda Protestan Por Pagos.” PROVEA. Accessed October 6, 2023. El Universal: Obreros de la Misión Vivienda protestan por pagos – PROVEA.

https://archivo.provea.org/actualidad/derechos-sociales/derechos-laborales/el-universal-obreros-de-la-mision-vivienda-protestan-por-pagos/

• Ministerio del Poder Popular para el Proceso Social de Trabajo – MPPPST. (n.d.). http://www.mpppst.gob.ve/mpppstweb/index.php/ministerio/

• Penfold-Becerra, Michael. “Clientelism and Social Funds: Evidence from Chávez’s Misiones.” Latin American Politics and Society 49, no. 4 (2007): 63–84. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30130824.

• Sánchez, Carlos Eduardo. “Venezuela’s President Maduro Celebrates Milestone: 4.6 Millionth House Completed under GMVV Program.” Orinoco Tribune – News and Opinion Pieces About Venezuela and Beyond, July 22, 2023. https://orinocotribune.com/venezuelas-president-maduro-celebrates-milestone-4-6-millionth-house-completed-under-gmvv-program/.

• Thelwell, K. (2019, December 12). 10 Facts about slums in Venezuela. The Borgen Project. https://borgenproject.org/10-facts-about-slums-in-venezuela/

• Toothaker, Christopher. Associated Press “Chavez Struggles to Fix Venezuela’s Housing Crisis.” Tribune, December 27, 2011. https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/sdut-chavez-struggles-to-fix-venezuelas-housing-crisis-2011dec27-story.html.

• Univision. (n.d.). A casi cuatro años de la muerte de Chávez, la imagen de sus ‘ojos’ no deja de esparcirse por Caracas. Univision. https://www.univision.com/noticias/citylab-arquitectura/a-casi-cuatro-anos-de-la-muerte-de-chavez-la-imagen-de-sus-ojos-no-deja-de-esparcirse-por-caracas

• Velasco, Prof. Alejandro. 2015. Barrio Rising : Urban Popular Politics and the Making of Modern Venezuela. Oakland, California: University of California Press. https://web.s.ebscohost.com/ehost/ebookviewer/ebook?sid=0f7a72d5-43de-4f03-b440-6abcf6a36018%40redis&vid=0&format=EB

• “Venezuela : Venezuelan working class is favored with the award of decent housing.” Mena Report, July 24, 2023, NA. Gale Business: Insights (accessed October 6, 2023). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A758296950/GBIB?u=nysl_ce_hamilton&sid=bookmark-GBIB&xid=44ad4c4c.

• “Venezuela: Great Housing Mission Venezuela, a benchmark for social inclusion of the Bolivarian Revolution.” TendersInfo News, 8 May 2023, p. NA. Gale OneFile: News, https://go.gale.com/ps/retrieve.do?tabID=T004&resultListType=RESULT_LIST&searchResultsType=SingleTab&retrievalId=6e7ffb07-fc3f-43f9-8262-dc2953df1e4a&hitCount=118&searchType=BasicSearchForm¤tPosition=1&docId=GALE%7CA748919447&docType=Article&sort=Relevance&contentSegment=ZNEW-FullText&prodId=STND&pageNum=1&contentSet=GALE%7CA748919447&searchId=R5&userGroupName=nysl_ce_hamilton&inPS=true&aty=ip. Accessed 6 Oct. 2023.

• Wetter, Yaneira Wilson. “The Eyes of Chávez.” ReVista (Cambridge) 20, no. 3 (Spring, 2021): 1-19. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/eyes-chávez/docview/2583135556/se-2.